Piano Intervals

What are intervals in piano? You’ve likely heard the term before, but you may not know what it means or how to apply it. To start, let’s take a look at these guiding questions:

Do you know what an E-7b5 chord looks like? How about a Cmaj7#11? The numbers in those chord names are intervals and knowing what those numbers represent allows you to easily read any lead sheet, as well as name your own chords so that you can communicate with other musicians about what you’re doing so they can play along.

When you are a beginner piano student, learning these intervals is the key to identifying complex new chords. But even for more advanced musicians, learning the intervals in a systematic way can help to increase the variety of your playing to help you break out of simple chord loops, find new chords to use, and improve your improvisation as you find new ways to transition from one chord to another. Also, this will help you learn an important piece of the language of music theory, kind of like how learning the name of every square on a chess board helps you speak the language enough to start reading the theory books and understanding what they mean.

What is an Interval in Piano?

An interval is the name of the distance between two notes. When you start taking beginner piano lessons, this is an essential piece of vocabulary to learn to start to discuss chords, as well train the ear — with the end goal of being able to pick out the melodies of popular songs.

Each name for an interval comes in two parts – the size and the type. The size is determined by the distance between two note names, and the type is determined by the type of note (i.e., sharp, flat or natural).

There are five types of intervals:

diminished

minor

perfect

major

augmented

This vocabulary can get somewhat confusing, especially when you start learning piano, so the two most important pieces of information you should take out of this blog about intervals in music are these:

1.) There is a name for the distance between any two notes on the piano

2.) The reason that some intervals only come in perfect, and others in major and minor, is because of physics (which will be explained later in the post).

Musical Interval Vocabulary

Half-steps:

A half-step (or semitone as it is also called) is the note directly next to the note you are coming from. For example, a half step down from A is Ab, and a half step up from F is F#.

Flats vs. Sharps:

A flat is the note one half-step to the left of a note, and a sharp is the note one half-step to the right of a note. These terms can be used as verbs as well, to flat something means to lower it one half step, and to sharp something means to raise it by one half step. In the chord mentioned at the beginning of the blog, a Cmaj7#11 (containing C, E, G, B and F#), the 11 is being sharped, meaning it is raised on half step. In this case, the 11th is an F, and then the F is sharped, so you add an F-sharp to a Cmaj7 chord (containing C, E, G, and B). Keep reading for a more detailed explanation.

Consonance vs. Dissonance in music:

When an interval is consonant, it sounds pleasing to the ear. When an interval is dissonant, it sounds harsh and grating to the ear. Some intervals are very clearly consonant, like a perfect octave, or a perfect fifth, while some intervals are clearly dissonant, like a minor second, an augmented fourth, or a major seventh. Some intervals are more in between, so consonance and dissonance are more like qualities than categories.

Both consonance and dissonance are used in music – the tension that dissonance creates is a key driver in moving a song or piece forward, while consonance is used to create a feeling of calm. The interplay between consonance and dissonance is at the heart of interesting compositions.

Major vs. Minor Intervals:

Unlike major/minor keys, or chords, in which major means that it has a bold, happy quality, and minor means that it has a sad, pensive quality, major and minor in intervals just has to do with the number of half steps. For example, both a minor second and a major seventh have a dissonant quality, even though one interval is a “major” and one interval is a “minor.” Check the chart in the next section for all the names of intervals.

What are Perfect Intervals?

There are three perfect intervals – the perfect fourth, the perfect fifth, and the perfect octave.

The reason some intervals come in perfect (unisons, fourths, fifths, and octaves) and the rest come in major and minor is because of physics. Each note has a specific frequency – for example, A4 sounds at 440Hz. The next A, a perfect octave above, at A5, is at exactly double that frequency – 880Hz. The ratio of frequencies in a perfect octave is always 1:2 (meaning the bottom note will have a frequency that is half that of the top note).

The ratio of frequencies in a perfect fifth is 2:3 (meaning the bottom note will have a frequency that is 2/3 of the bottom note), and in a perfect fourth it is 3:4 (meaning the bottom note will have a frequency that is ¾ of the top note). For example, a perfect fifth above A5 (at 440HZ) is E5 – which sounds at 660Hz (2/3 of 660 is 440).

These perfect intervals are found in every culture across the world, because of these perfect ratios. Different musical traditions disagree on the number of notes between these perfect intervals (some cultures in the Middle East and India, for example, have quarter sharps and flats) but the perfect intervals are common to all. Try it yourself! Play some of these intervals and hear for yourself how the perfect intervals are just more consonant than the other intervals. You don’t need advanced measuring techniques to figure out that these intervals just sound good, and indeed they didn’t have those measuring techniques long ago, and still found these intervals due to their consonant sound. Here is more information about different note divisions in an octave such as in Indian classical music and Arabic music, why it is that western music has the twelve divisions we are used to, as well as some other cool info about note divisions.

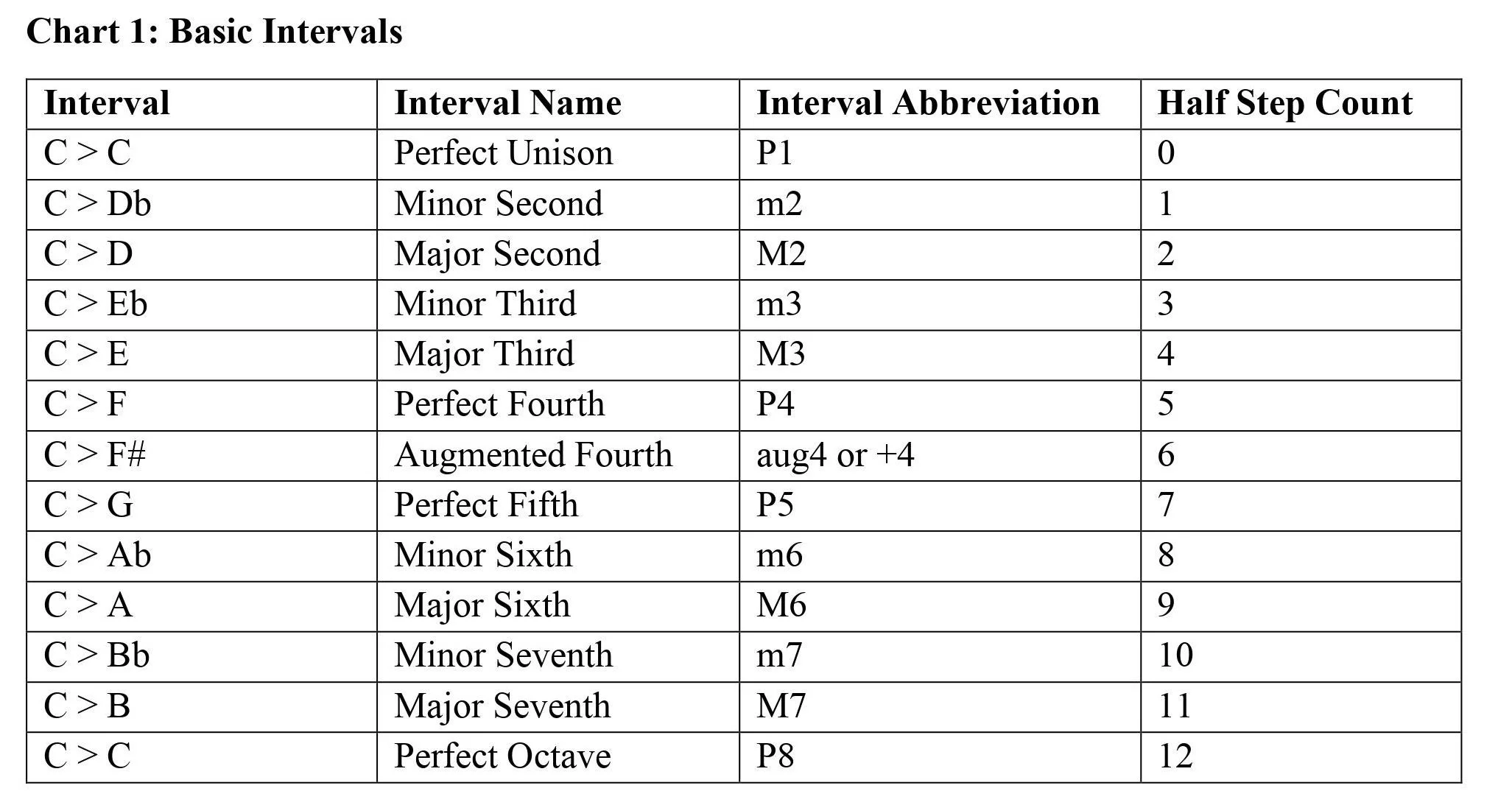

As you can see, both intervals from C to A (C to Ab, and C to A) are sixths, but C to Ab is a minor sixth, and C to A is a major sixth. Here is the full chart of all intervals.

Extended Intervals:

Any intervals larger than a perfect octave are called extended intervals. They are how jazz chords are named when they are more complicated than a regular seventh chord – such as the Cmaj7#11 that was mentioned at the beginning of this blog, and many other examples such as G7b9 (containing G,B,D,F and Ab), F6/9 (containing F, A,C,D,G), etc. (basically anything with a number at the end greater than 7).

The reason that these chords are named this way is because the chord that they are built on top of is simple (In Cmaj7#11, for example, the base chord is a Cmaj7), and the number after is an extension that goes above the chord (#11 is an extension on top of it). Every extension has an analogous interval to it, as labeled in the chart below.

As you can see, the pattern of interval names is the same as in the basic intervals in the first chart with these extensions, which makes sense as it is just going to the same notes but one octave above. You can technically continue going with intervals more than one octave above the basic intervals, but they are not widely seen as the first set of extensions in the chart above is enough to name almost any chord.

Augmented & Diminished Intervals

To augment something is to add to or make larger, and to diminish something is to take away from or make smaller. With intervals, an augmented interval is an interval larger than the basic ones in the first chart, and diminished is an interval smaller than the ones in the first chart.

The most common intervals, and the ones that naturally occur in natural major and minor keys, come in the type of major, minor, and perfect. However, there are two more that occur as well – augmented and diminished.

As you can see, there are augmented and diminished types of every interval (unlike major/minor and perfect, where it’s one or the other), but they don’t occur nearly as often. The second interval in the table, C to Dbb is very rare, as Dbb is just C, so it’s a normal perfect unison.

So why do the names of these intervals exist in the first place? This is because of how chords are formed. So, for example, any C chord, whether major, minor, augmented, or diminished, will have some form of the notes C, E, and G.

A C major chord is made up of a major third and a perfect fifth above C, so C, E, and G.

A C minor chord is made up of a minor third and a perfect fifth above C, so C, Eb, and G.

An augmented chord is made up of a major third and an augmented fifth above C, so C, E and G#.

A diminished chord is made up of a minor third and a diminished fifth above C, so C, Eb and Gb.

Because a C chord has to be made of C, E, and G, to make a diminished chord, you have to make a chord even smaller than a minor chord, so you flat the G into Gb. And to make an augmented chord, you have to make a chord larger than a major chord, so you sharp the G into G#.

If you’ve been paying attention, you’ll have figured out that a G# is the same as Ab, meaning an augmented fifth has the same number of half steps (and ends up on effectively the same note) as a minor sixth. So why are there two different names for the same interval? This is because of how chords are formed – a C chord must contain a C, E, and G, or it is not a C chord anymore. If you renamed the G# of the augmented C chord to Ab, you would now have an A chord, not a C chord, as the notes would now be Ab, C, E. All A chords must contain an A, C, and E, just like all C chords must contain a C, E, and G.

Why is learning about intervals important for piano?

Learning the names of piano intervals is most useful to start to understand the language of music that allows you to communicate more effectively with other musicians. Think about it, is it easier to tell people that you are playing a C7b9 chord, or to name all five notes in that chord (C, E, G, Bb, Db)? It is of course easier to just name the chord, and when you get more advanced, there are certain scales that are more effective when played over certain qualities of chords than others, so when you are improvising, knowing the names of the chords makes your improvisation much easier.

Another use for intervals, and memorizing them, is for singing. If you are in a choir, and you have to learn a song very quickly, knowing what a perfect fourth sounds like, or a major sixth, makes it easy to sing a song directly from the sheet music, without having to first play it on another instrument to get the notes and then sing it.

Practicing ear training with intervals makes it much easier to start picking out melodies by ear on the piano as well – knowing that the singer is singing a perfect fifth in that jump means you know what note to play next and takes the guesswork out of it.

Intervals are the vocabulary of the music world, but learning the vocabulary makes it much easier to speak the language of music and will really enhance your ability to understand and communicate with music and music theory. For advanced and beginner pianists alike, understanding intervals will make the piano keyboard much clearer!

Want to go over the fundamentals of music theory in more depth with the careful guidance of an instructor? Sign up for private piano lessons near Malden to get your musical journey underway!